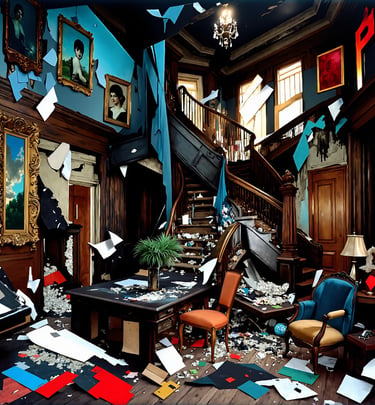

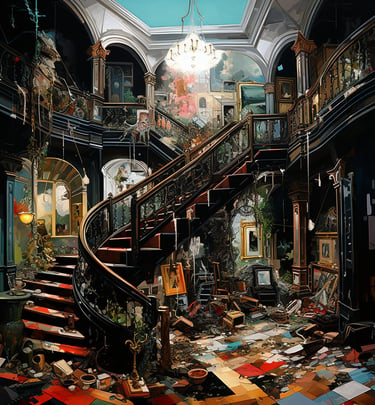

Studio Ruins

These rooms are not studios. They are collector spaces. The ornate architecture with its gilt mirrors, crystal chandeliers, and elaborate moldings belongs to the world of galleries, auction houses, and private collections. The walls look perfect because they only hold finished work, the kind that gets treated like an investment or a luxury object once it leaves the artist’s hands.

The floor tells a different story. This is where the damage settles. Torn canvases, abandoned studies, scraps of color tests, and all the remnants of work that never found a place to land. It is the physical evidence of every artist who kept producing, kept trying, and still could not survive in the system that depends on their labor. The art world needs the work, but it rarely cares about the worker. That is the divide these rooms try to show. Everything above eye level is pristine. Everything below it is a quiet collapse. The chandelier is spotless. The collector gains. The artist bleeds on the floor.

This is the blood of the artists the market refuses. They may have skill, discipline, vision, and decades of practice, but they lack the gallery connection or the social alignment that decides who becomes visible. Their work is serious. Their effort is sustained. Yet in a system where art often functions as a financial instrument instead of something necessary to culture, survival is reserved for the few who fit whatever narrative the ruling class happens to value that year.

It is a bit like the story of Dorian Gray. The polished surface stays perfect because the decay is pushed somewhere else. These rooms bring that hidden surface into view. They show the cost of keeping the collector’s world clean. Someone has to absorb the damage, and it is almost always the people who make the work.

The rooms ask a simple question that has no simple answer. What happens to the artists who did everything right, who built a serious practice, who worked for decades, and still could not make a living? Where does that blood go when the only thing that matters in the end is the finished object hanging under the chandelier?

Doppelgänger

Identity is not a single thing. It shifts the moment someone looks at it.

The figures in this series exist in doubled states. They stand beside versions of themselves that feel a little too close, reflections that do not completely align, selves that seem to watch each other with a kind of caution. A doppelgänger does not offer comfort. It opens a crack. It makes you aware that the self you show the world might not be the self that actually exists, and that identity is something you perform rather than something you own.

These images borrow visual language from Dutch master portraits and Victorian photography. The centered figures, the deep backgrounds, the direct gazes all recall traditions that tried to capture and confirm who someone was. The doubling complicates that idea. The mirror does not confirm identity here. It reveals the instability inside it. It turns the question of who you are into something unsettled.

Motifs repeat across the series. Flowers passed between two figures. Matching expressions on faces that are not quite the same. Bodies that look mirrored until you notice a subtle shift in dress or posture. All of this suggests that selfhood is something relational, not solitary. We understand ourselves partly through an other who resembles us and yet remains separate. The doppelgänger becomes the self we might have been, the self we worry about becoming, or the self we cannot comfortably align with the person we believe we are.

Sometimes the doubling is literal, like identical twins or perfect reflections. In other images, it works on a psychological level. You see two versions of the same person divided by a small shift in expression or by a costume change. The same question runs through every variation. Which one is real? Or are both performances shaped for an audience that now includes the other self, the one looking back from inside the image?

These portraits sit inside that instability. Once observed, the self divides. It multiplies. Versions look at each other across the frame, unwilling to settle on who comes first. The flowers that appear again and again can read as offerings or accusations. They move between selves that cannot decide if they are in conflict or in conversation.

The work offers no final answer. There is no hidden, authentic self waiting underneath the surface. There are only versions, each constructed in the same way the period costumes and formal poses are constructed. The doppelgänger simply reveals what portraiture has always concealed. The moment we are seen, we become something shaped by the act of looking.

Contact

Reach out for commissions or course info

valeriacsizmadia@gmail.com

© 2025. Parallax Studio